No Fee Unless You Win

No Fee Unless You Win

Preventable medical errors kill and injure millions of Americans every year. In fact, death by medical error is the nation’s leading cause of accidental death. Its death count exceeds that of strokes, chronic lower respiratory diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, and diabetes. In fact, estimates are that preventable medical errors contribute to the deaths of around 200,000 Americans in hospitals every year (there are no estimates for those who die outside of U.S. hospitals).

In many cases, responsibility for medical errors lies with healthcare providers who deviate from accepted standards of care. These errors can range from surgical mistakes and misdiagnoses to delayed treatment or medication mix-ups. When a provider’s negligence directly leads to injury or death, the law may recognize this as medical malpractice.

Understanding when a medical error becomes malpractice is crucial for both patients and their families. Not every error results in legal liability, but if the mistake would not have occurred under competent care, and if it caused measurable harm, it could meet the legal threshold.

From there, how malpractice damages are calculated depends on the severity of the harm, the financial losses incurred, and the long-term impact on a patient’s life. Arizona courts consider both economic and non-economic damages when evaluating these claims, including medical costs, lost wages, and pain and suffering.

One American dies in a hospital every 2 minutes and 30 seconds from preventable medical errors. That makes it an epidemic and serious public health problem. Yet, how often do you hear about this on the news? How often do you hear politicians asking for billions of dollars to reduce the number of deaths? People barely tolerate one error in a restaurant order when determining if they will come back, so why do we tolerate so many fatal errors in the health care industry?

Maybe it’s because we don’t understand medicine or are constantly bombarded with propaganda about “frivolous lawsuits.” Health care lobbyists and advocacy groups would have you believe preventable medical errors are rare and that people who sue for medical malpractice are greedy liars. These groups question statistics about preventable medical errors. They do not challenge that an error was made but, instead, challenge whether the error was the sole cause of death (or if the person was going to die anyway)—ignoring tens of thousands of cases where the preventable medical error contributed to the patient’s death.

The financial and emotional costs are not limited or self-contained. The health insurance industry spends billions of dollars every year covering care necessitated by preventable medical errors. Your insurance premiums and tax dollars subsidize a health care industry that financially benefits from its mistakes (i.e., necessitating additional in-patient days and further medical care).

The sad reality is that only 2% of people who suffer from medical errors seek a civil remedy. The vast majority of claims injury victims assert involve catastrophic injuries or death. The most common source of medical malpractice claims is diagnostic errors. The second most common source of medical malpractice claims is surgical errors. The financial costs of these errors can overwhelm their victims. For example, the average cost of care for birth injuries exceeds $2.5 million. Consequently, families who lose a loved one often suffer economic losses exceeding $1 million.

Only 2% of people who suffer from medical errors seek a civil remedy, and they face many hurdles along the way

| Statistic | Detail |

|---|---|

| Medical error-related deaths per year | Estimated 250,000 to 440,000 |

| Frequency of fatal errors | 1 death every 2.5 minutes |

| Common types of errors | Misdiagnosis, surgical mistakes, medication errors |

| Patients who take legal action | Only 2% of those harmed |

| Medical malpractice insurance premium (average) | $7,500 per year |

| Average hospital doctor salary | $460,000 per year |

Medical errors are a leading cause of preventable death in the US, yet few victims ever seek compensation. Despite the human toll, doctors pay relatively low malpractice premiums compared to their salaries, and legal caps make it difficult for injured patients to recover full damages.

Here’s another depressing fact. Most health care providers only carry $1 million in medical malpractice coverage and have their assets heavily protected, if not completely shielded from exposure. In other words, most medical malpractice victims are undercompensated for their economic and non-economic losses. Some publications suggest doctors and hospitals avoid paying up to 80% of the total harm their errors inflict. One disgusting aspect of underinsured health care providers is that the average medical malpractice insurance premium costs only $7,500 per year. Keep in mind the average hospital-based physicians make $460,000 per year.

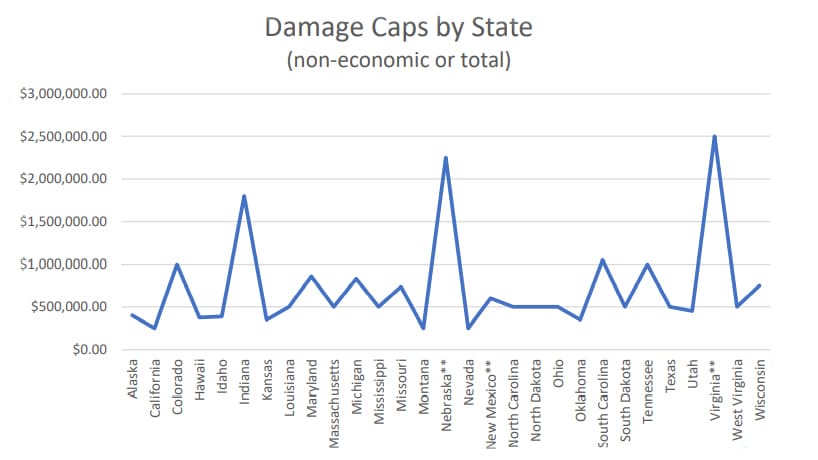

Politicians and lobbyists line their pockets despite the inequities caused by preventable medical errors by further sticking it to injury victims. Most states created hurdles to pursuing medical malpractice claims by enacting laws to increase the costs of bringing a medical malpractice claim and decrease the potential amount of money a jury may award. For instance, many states capped non-economic damages—those damages intended to compensate you for pain, suffering, disability, disfigurement, scarring, and loss of enjoyment of life—as low as $250,000; with some states being even more draconian by capping total damages—economic and non-economic—as low as $500,000.

Such caps are arbitrary and should be unconstitutional.

Imagine you have an athletic 14-year-old child who loves sports, plays an instrument, and is active in caring for your parents. Then, they accidentally break their arm, requiring surgery. Your child should recover to pre-injury ability, but the surgeon commits a preventable medical error that results in your child losing their arm. All hopes for the future, dreams, and aspirations of continuing to play sports and an instrument were cut short. In states that enacted damage caps, your 14-year-old child might only be able to collect $500,000. Put another way, your child’s compensation for the next 65 years of discomfort, phantom pain, disability, loss of enjoyment of life, and fears about work, relationships, and safety could be limited to $250,000—less than $4,000 per year. Would you voluntarily lose a limb for $4,000 per year? What if that child died? Would you feel fairly compensated with $250,000?

States with caps are not better at compensating victims or their families. Medical error victims often must hire an attorney to help them pursue their claim, which also requires the expenditure of $100,000 or more in litigation costs (e.g., medical experts, forensic examiners, economists). Then there’s the kicker that most injury victims are required to reimburse their health care insurance company for injury-related care it covered—thank your congress members for that. Further magnifying the obstacles for injury victims, some states and the federal government passed laws statutorily limiting the amount attorneys can charge. The limits on attorneys’ fees can make it difficult for injury victims to find an attorney willing to spend hundreds of hours and hundreds of thousands of dollars to help them pursue the case. Ultimately, with these oppressive laws, everyone else is getting paid but the injury victim.

Death by medical error is the nation’s leading cause of accidental death. Its death count exceeds that of strokes, chronic lower respiratory diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, and diabetes.

These inequities might explain why the number of malpractice claims lodged every year has steadily decreased since the 1990s, despite the number of preventable medical errors staying steady. The decrease in medical malpractice claims is not because the quality of care has increased. Having worked around the health care industry since the 1990s, I can say with confidence:

One troubling aspect of the last three points is that even if the hospital investigates a medical error, neither the patient nor their family will receive details of its findings. This obfuscation is part of the “Peer Review Protection.” All 50 states and the District of Columbia enacted laws protecting hospitals’ peer review activities, designed to encourage participation by minimizing legal risks. The protection is such that, during the peer review process, a health care provider can admit to making a preventable medical error but then deny any wrongdoing in a civil suit brought by the injury victim or the family.

A good medical malpractice attorney can sometimes get the health care provider to acknowledge they made a mistake, but that does not mean the provider will admit they were negligent. Many times, when mistakes are acknowledged in civil litigation, the health care provider characterizes the mistake as “clinical judgment,” “an honest mistake,” or “a medical mishap.” The defense further tells the jury that the health care provider devoted their career to helping people and what happened was a recognized risk of treatment. The health care industry likes to claim that known risks of injury are the patient’s problem when they occur, and providers are not responsible for preventing those injuries.

Ultimately, the health care industry is about making money for executives, managers, doctors, investors, and even insurance companies. As restaurants and small businesses regularly go out of business, doctor’s offices and clinics are popping up everywhere. There is a lot of money in health care, and no one wants to cut into profits by paying for preventable medical errors. Sadly, the health care industry is often successful in avoiding paying for its errors. Their success provides a quasi-immunity in the civil justice system. Past success encourages the health care provider to force injury victims and their families to prosecute cases, sometimes for years, even when there is clear liability. Health care providers and their attorneys hope the jury will either be confused, dislike the injury victim, or fail to appreciate the true value of the harm inflicted—situations that usually lead to defense verdicts or unreasonably low verdicts.

There are two justice systems in America: civil and criminal. We’ve seen how the civil justice system protects health care providers who make preventable errors. What about the criminal justice system?

The criminal justice system largely ignores the health care industry. Unsurprisingly, most criminal charges in the health care industry center on financial crimes and fraud. In other words, even the criminal justice system focuses on protecting money and profits. The criminal justice system focuses a lot of attention on punishing people who take money from insurance companies, the government, or investors and very little attention on health care providers who injure their patients.

There are the rare cases where health care providers spend time in jail for hurting patients. Unfortunately, these cases usually only involve the most egregious and outrageous circumstances. For example, the nursing assistant who intentionally killed elderly patients at a Veterans Affairs Hospital, a nurse who sexually assaulted a woman in a vegetative state at Hacienda HealthCare in Arizona, and a Tennessee doctor who illegally distributed opioids from clinics. Then there’s the infamous case of Christopher Duntsch, also known as Dr. Death. In 2017, he was sentenced to life in prison after maiming and killing 33 of his 37 patients from 2011 to 2013 because he was grossly incompetent to the point he knew or should have known his actions were causing injuries.

Despite killing and maiming more people than street gangs, more kids than school shootings, we do not police hospitals and other health care institutions—except for financial crimes. How often have you heard the president or leaders in Congress implore the American public to support improving the health care industry to eliminate preventable errors?

We’ve shown you the statistics that undermine the claims that only a few health care providers are responsible for most errors. But, even if they are right and everyone else is wrong, think about how Christopher Duntsch was allowed to significantly injure and kill 33 patients over almost three years. You need to ask yourself, why was he able to maim and kill so many people. Why was he able to operate with impunity?

The easy answer is that hospitals make a lot of money from neurosurgery.

The easy answer is that hospitals make a lot of money from neurosurgery. Neurosurgery is a top 3 revenue source for hospitals, bringing in annual revenue averaging around $3.5 million per year. Also, the U.S. has around 6,000 hospitals, but there are only around 3,500 practicing board-certified neurosurgeons. This disparity is huge and allows hospitals to advertise their unique expertise in this field of specialty. Can a hospital really afford to lose one of a few neurosurgeons after a few “mishaps?”

The answer is complicated.

When hospitals realized Christopher Duntsch was more of a liability, they allowed him to “resign” rather than fire him. The significance of this professional courtesy is that the hospital did not have to report him to the National Practitioner Data Bank, a national repository tracking doctors’ discipline and malpractice settlements, or the Texas Medical Board.

Keep in mind, Texas has peer review laws that protect those who report misconduct and those who participate in the peer-review process. The purpose of the medical peer review privilege is to “promote the improvement of health care and the treatment of patients through review, analysis, and evaluation of the work and procedures of various medical entities and their personnel.” The lie they tell is that this privilege and confidentiality are necessary to protect the public. Peer review proceedings are shrouded in secrecy, and everything related to the process is kept confidential. The health care industry tells us this secrecy is necessary to ensure “free discussion in the evaluation of health care professionals and health services.”

If you did not know the story of Christopher Duntsch, and you believed the peer review process advocates, you would expect that Texas’s peer review process intervened and protected the public after only a handful of preventable medical errors. And you would be so wrong. The Texas hospitals and medical board did not do anything about Christopher Duntsch for several years and only stepped in after it was too late for 33 patients. Why?

Medicine developed a culture of silence, especially when dealing with patient injuries. Health care workers who witness preventable medical errors frequently stay quiet. Their silence is ingrained in their industry either out of respect for their coworkers, fear of reprisal, fear of exposing their employer to civil liability, or fear of losing a career they worked so hard to obtain. Over time, numerous nurses, operating room staff, and physicians saw what was happening to Christopher Duntsch’s patients and did not speak up. Leaders failed to address any of the medical errors in a preemptive fashion. No amount of peer review privilege could overcome the culture of silence.

Medical malpractice lawyers will tell you that the conduct in many of their cases rises to the level of recklessness, but none of the perpetrators were charged criminally. Law enforcement does not roam the halls of hospitals enforcing patient safety rules. The police are not giving out tickets when health care providers increase the risk of harm to patients. State and local law enforcement ignore the potential criminal aspects of health care delivery in every city, county, and state.

In Arizona, you can be guilty of negligent homicide if you caused the death of another person when you should be aware of a substantial and unjustifiable risk that a person could die from your conduct. Some call this “gross negligence,” which is essentially acting in reckless disregard for the safety of others. A person is reckless if they act without thinking or caring about the consequences of an action. But, again, when it comes to health care providers injuring patients, law enforcement appears to have a policy to look the other way.

Some people in the health care industry fear law enforcement is about to change that policy. I fear it never will.

In 2022, former Nashville nurse RaDonda Vaught was found guilty of negligent homicide and gross neglect of an impaired adult. Many people in the health care industry publicly decried the conviction. Ms. Vaught received an outpouring of support from countless health care industry members. Those who supported her also made it sound like the world was imploding. The reaction was somewhat akin to a deity losing its invincibility and being forced to confront mortality for the first time. But the reaction ignores the facts of what Ms. Vaught did and perpetuates the culture of silence.

Importantly, Ms. Vaught did not intend to kill 75-year-old Charlene Murphey.

While preparing Ms. Murphey for a radiology study, Ms. Vaught was supposed to give Ms. Murphey a sedative. Instead, she administered a powerful paralytic medication that prevented Ms. Murphey from breathing. Unable to breathe, Ms. Murphey lost consciousness, suffered an anoxic brain injury, and subsequently died. Immediately after Ms. Murphey was discovered unconscious, Ms. Vaught admitted to hospital staff that she had made an error. Two hospital neurologists verified Ms. Murphey’s death and notified the county medical examiner, but they did not mention the medication error. Culture of Silence? Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) then took steps to hide the fatal medication error from the government and the public. Culture of Silence? The hospital secretly and confidentially settled the civil claim with Ms. Murphey’s family, preventing anyone from publicly disclosing what happened. Culture of Silence?

It didn’t take long before an anonymous person notified the Tennessee Department of Health, the agency responsible for licensing and investigating medical professionals. The agency determined the event “did not constitute a violation of the statutes and/or rules governing the profession” and did not merit further action. Culture of Silence?

The anonymous person also notified the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which conducted a surprise investigation. CMS issued a public report threatening to suspend VUMC from participating in Medicare if it did not take steps to prevent similar errors. This is HUGE. Medicare payments are usually a significant portion of a hospital’s revenue stream. Losing payments from Medicare would cripple VUMC’s ability to function. So executives quickly developed a plan.

Ms. Vaught was arrested a few months after the CMS report went public. Police charged her with reckless homicide and abuse of an impaired adult.

Court records revealed Ms. Vaught allegedly made 10 separate errors when giving the wrong medication to Ms. Murphey. Most modern hospitals have a fancy electronic system that carefully monitors and controls medication orders and administration. It is called a “medication dispensing cabinet.” The medication dispensing cabinet requires the nurse to find the patient’s profile in the system and then select the medication the nurse wants to administer. Ms. Vaught pulled up Ms. Murphey’s chart. She searched for “ve” looking for Versed (a sedative), but nothing came up. Ms. Vaught should have contacted the pharmacy to verify the prescription. Instead, she clicked the manual override function, which allows access to all medications in the system, including those not prescribed for the selected patient. Error #1.

In manual override mode, Ms. Vaught searched again for “ve” and selected the first medication on the screen. It was vecuronium, a powerful paralytic often used for emergency intubation. Vecuronium is used for emergency intubation because it is quick-acting and prevents patients from fighting intubation. It turns out that Ms. Vaught was not using the generic name for Versed. Error #2. Important note: Versed is a liquid and vecuronium is a powder. When Ms. Vaught obtained the medication, she did not question that it was a powder. Error #3. Ms. Vaught did not double-check to verify she had the correct medication. Error #4.

When Ms. Vaught selected the medication, at least three screens on the medication dispensing cabinet alerted: WARNING PARALYZING AGENT. One of these screens had a yellow alert banner. Ms. Vaught was required to provide a reason for using the override function and indicate how many vials she removed. She did so, ignoring the alerts. Error #5. After administering the paralytic agent, Ms. Vaught left Ms. Murphey alone and unmonitored. Error #6.

Objectively, her conduct was reckless, dangerous, and caused Ms. Murphey’s death.

In the criminal case, the defense was that the two medications had similar names, vecuronium and Versed, and that Ms. Murphey made an honest mistake. I cannot tell you how many times I’ve heard defendant health care providers and their experts say in civil litigation, “It was an honest mistake,” “it could have happened to anyone.” When they say that, I hear, “Oops. My bad.”

Ms. Vaught’s conduct was not a simple “oops.” Instead, Ms. Vaught’s conduct was a “never event,” defined by the National Quality Forum as “errors in medical care that are clearly identifiable, preventable, and serious in their consequences for patients, and that indicate a real problem in the safety and credibility of a health care facility.” Her criminal trial resulted in a conviction, and she faces several years in jail.

After the verdict, the American Nurses Association issued a statement that mimicked Ms. Vaught’s defense after the verdict. Additionally, the ANA decried the conviction as setting a dangerous precedent by “criminalizing the honest reporting of mistakes.” With a frightening coldness, the ANA considers Ms. Vaught’s conduct as an “inevitable” medical error. Another troubling aspect of the ANA’s statement is the suggestion that there are more “effective and just mechanisms” to address similar conduct than criminal prosecution. Again, the ANA is out of touch with reality. There were mechanisms in place to prevent Ms. Vaught from doing what she did to Ms. Murphey.

Here’s the part that might surprise you. I feel bad for Ms. Vaught. Not in the way where one might forgive and forget what she did, but in the way where one is angry because what happened was not all her fault.

The Tennessee Department of Health, the same agency that previously declared no further action necessary, declared Ms. Vaught a “threat to the public” after being charged with a crime. Ms. Vaught was not a threat to the public. In the situation she was in, at that specific instance, she was a threat to Ms. Murphey and only Ms. Murphey. The threat to the public was VUMC, which I’ll explain in a moment.

During the criminal trial, Assistant District Attorney Chad Jackson said Ms. Vaught was worse than a drunk driver who killed a bystander because it was as if she were driving with her eyes closed. The prosecution also described Ms. Vaught as irresponsible and uncaring. I think the prosecutor was being a little dramatic. Ms. Vaught was in full control of how she had to maneuver to get her job done. Her eyes were wide open. But I do not believe Ms. Vaught made an honest mistake, and, as you will see, neither does she.

Ms. Vaught’s defense attorney, Peter Strianse, may have been onto something when he said she became a “scapegoat” for systemic problems related to the medication cabinets at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in 2017.

Vanderbilt University Medical Center is a large independent non-profit organization with academic affiliations with Vanderbilt University. It has hospitals, clinics, physician practices, and affiliates covering nine hospital systems and 48 hospital locations, serving an extensive patient base. As previously mentioned, once the CMS report became public, this became a serious issue. For the second time in less than five years, VUMC was in trouble with CMS (i.e., in 2014, the federal government sued VUMC for Medicare fraud).

VUMC received approximately 22% of its net revenue from Medicare. Losing that much funding on a regular basis could have forced VUMC to shut down numerous facilities and stop offering services in some specialties. The potential unemployment of executives and over 16,000 staff members is too much to imagine. Plus, all those patients would have to find care elsewhere. In addition, stakeholders would not have been happy with the Board of Directors and executives.

Who would stand up, raise their hand, and accept responsibility for such a failure? Clearly not the Board of Directors or its executives. After all, the hospital’s coverup was probably the only reason this case became public. The coverup angered CMS. VUMC’s failure to implement safeguards or further training after Ms. Murphey’s death is probably why there was an anonymous tipster.

I don’t ascribe to conspiracy theories, but I can see a scenario where the enormity of the potential fallout led hospital executives to meet with politicians to discuss how to fix the problem. Keep in mind, District Attorneys must be elected by the public. Winning high-profile cases gains district attorneys and assistant district attorneys a lot of brownie points in the minds of voters and prospective employers.

Arguably, what happened to Ms. Murphey could have happened to any patient, and therefore everyone was at risk. They needed to send a message to the public that they were focused on public safety and eliminated the risk.

Changing policies and agreeing to do better in the future would not be enough. For this reason, the public needed a boogeyman. A demon who could be exorcised from the hospital. The hospital identified the boogeyman and arrested her.

Don’t believe me? Look back at the timeline.

Did you notice something peculiar? The Tennessee Bureau of Investigations did not interview Ms. Vaught until after the CMS report became public.

Will prosecuting individual health care providers make medicine safer? Probably not.

My discussion about this case highlighted several factors that led me to conclude this criminal conviction is a one-off. It is the exception, not the norm. Tennessee had no intent to criminalize what happened to Ms. Murphey until CMS publicly threatened to pull funding from VUMC. Only then did Ms. Vaught receive any attention for what happened, despite admitting to her error a year earlier. Also, not to denigrate hard-working prosecutors around the country, but they are not trained to prosecute health care providers for preventable medical errors, especially ones that require understanding the nuances of medicine and health care delivery.

In an article by MedPage Today, Dr. Jeremy Faust pondered that Ms. Vaught’s conviction could contribute to a culture of silence and that this silence “may make systemic problems less readily identified and rectified.” The culture of silence has existed since the advent of modern medical practice. It is ingrained in the culture of medicine. When we look at the facts, hospital staff were well aware of the systemic problems over a year before the CMS report and before Ms. Vaught was arrested. The culture of silence kept the cause of Ms. Murphey’s death fairly well hidden. Additionally, in the case of Christopher Duntsch, we saw how multiple layers to the culture of silence allowed him to keep maiming and killing patients.

Does Dr. Jeremy Faust believe the current system, where health care providers mostly enjoy immunity from prosecution and doctors like Christopher Duntsch are allowed to practice unchecked, is working? I don’t.

What happens next?

The nursing profession is short-staffed, strained, and enduring significant pressures, and the Covid pandemic is amplifying their problems; however, deeper issues need to be addressed.

Ms. Vaught tried to raise these deeper issues with the nursing board. At the time of Ms. Murphey’s death, the hospital’s medication dispensing cabinets were hampered by technical issues. The hospital upgraded its electronic health records system in 2017. According to her defense lawyer, a closer look at the hospital’s systems revealed a problem that prevented communication between the hospital’s electronic health records, the hospital pharmacy, and the medication dispensing cabinets. In other words, the hospital’s upgrade caused unnecessary and disruptive delays at the medication dispensing cabinets.

Staff became frustrated because this interfered with patient care. Ms. Vaught testified, “You couldn’t get a bag of fluids for a patient without using an override function.” Therefore, the hospital instructed nurses to use overrides to prevent delays and get medications quicker. At the time of Ms. Murphey’s death, overrides were standard practice at the hospital and part of everyday nursing practice at VUMC.

Systemic failures in the health care industry allow dangerous medical practices to proliferate without proper safeguards. The sad reality is that the health care industry is plagued with systemic errors, largely driven by profits over patient safety. For example, many health care organizations operate with minimum staff levels, which leads to increased demands on staff, pressure to do things quickly, and sometimes cutting corners to meet expectations. In addition, some health care organizations operate with broken or antiquated systems. Environments like this setup staff for failure. Management should know better than thrusting such conditions on its staff, and, when it does, it should be held accountable for the preventable medical errors that injure patients.

Individual health care providers are not in a position to discover systemic defects and develop solutions. That is a management function. Yet, civil and criminal justice systems tend to focus on the individual health care provider—the person who has no control over the systems that set them up for failure—and not management. Ironically, management might not have enough incentive to change the systems and improve health care delivery. As mentioned above, medical errors bring more revenue into the organization because of the additional care the harms require. Management will not stay employed if they cause the hospital to lose revenue.

In a moment of reflection, Ms. Vaught must have realized the obstacles presented by VUMC’s systems did not completely explain what happened to Ms. Murphey. She testified that she allowed herself to become complacent while using the medication dispensing cabinet and did not double-check which medication she had withdrawn.

Her use of the term “complacent” is important. Generally speaking, we see it across many industries. People tend to become complacent when they become very comfortable and familiar with their job. Often, the person becomes so secure in their work that they take potentially dangerous shortcuts, do not perform tasks to the same quality as they once did, or become unaware of deficiencies. It takes time.

I doubt Ms. Vaught would have been complacent had the hospital not made it standard practice to override the medication dispensing cabinet. She possibly would not have been complacent had management not had financial incentives to stay complacent. Ms. Vaught’s complacency, and complacency in general, is a management problem. Consequently, management should be doing more to identify and resolve complacency in its staff, especially when complacency increases the risk of harm to patients.

Systemic failures in our health care system do not excuse preventable medical errors, like giving the wrong medication or ignoring numerous warning signs. They do not excuse Ms. Vaught from becoming complacent and increasing the risk of harm to her patients. But after reviewing the facts, shouldn’t it be punishment enough that Ms. Vaught will live the rest of her life knowing that her actions caused the death of another person or knowing that she will never be permitted to work as a nurse again? She is not evil. She is not dangerous to the public. Is jail really necessary?

CMS is trying to foster patient safety by attacking incentives. It is trying to cut down on preventable medical errors by refusing to pay for subsequent injury-related care. We have seen the power of financial incentives, but I am not sure this one will be very effective. Health care providers are good at covering up mistakes, and the culture of silence is here to stay.

The above discussion addressed several individual and systemic failures in the health care industry. I’ve thought about potential solutions that might cover both failures and think two are worth presenting.

One solution is hinted at above—hold management and executives liable for preventable medical errors within their facilities and organizations, regardless of who committed the error. Open them up to potential civil and criminal liability. Management and executives are best positioned to implement safe systems, enforce compliance with safety protocols, and observe the system for weaknesses that require remediation. In other words, incentivize management and executives to ensure health care delivery revolves around patient safety.

The other solution requires a wholesale change in perspective, one that recognizes health care impacts almost every American on a daily basis and believes the health care industry should revolve around patient safety. Patient safety should be the first, second, and third goal of health care.

Capitalism and social pressures have been largely ineffective in focusing health care on patient safety. Therefore, government regulations should require the health care industry to maintain a culture that recognizes safety challenges, develops viable solutions to those problems, implements the solutions, and then assesses the success of those solutions. In addition, health care organizations must establish a culture of safety that focuses on constant systemic improvements by viewing medical errors as challenges that must be overcome and not liabilities that need to be avoided.

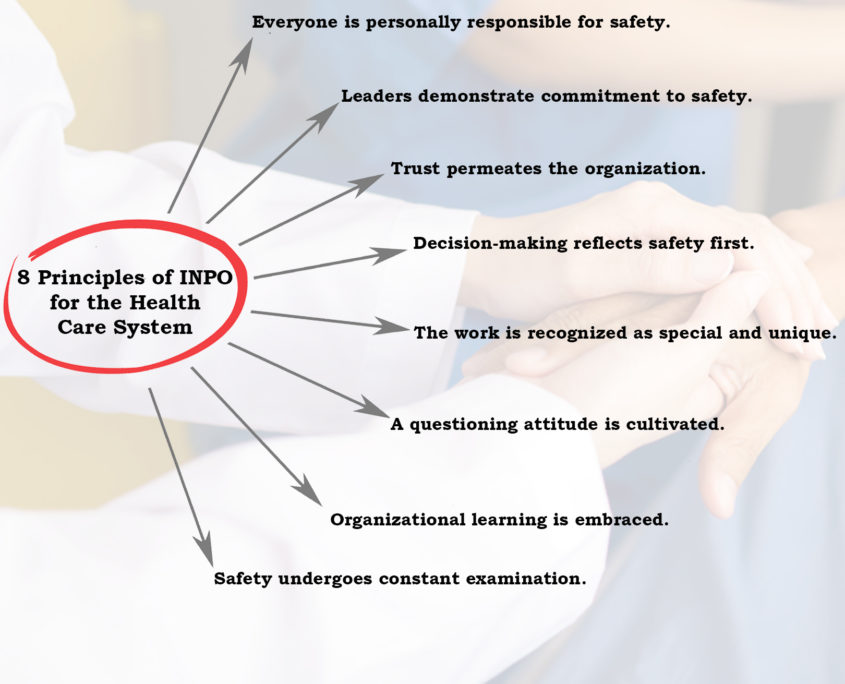

The health care industry could benefit from adopting the rules and regulations that govern the nuclear power industry. A culture of safety is part of the foundation of the nuclear power industry. The nuclear safety culture is the core values and behaviors resulting from a collective commitment by leaders and individuals to emphasize safety over competing goals to protect people and the environment. Everyone is responsible for nuclear safety, from the top-down. The safety culture aims to create a framework for open discussion and continuing evolution. For instance, it is welcomed and expected for nuclear power plant employees to correct the actions of their fellow workers, including supervisors, without retaliation or fear of reprisal. In short, this mindset requires training and reinforcement from management and executives.

To effectuate a strong safety culture, you can see that we need to eliminate peer review privilege and confidential settlements. For this reason, the health care industry needs to eliminate the culture of silence and focus on acknowledging medical errors, accepting responsibility for patient injuries, and working to avoid medical errors in the future. Obviously, all health care team members, including management, must play a role in making the provision of health care safer. Think of how many lives could be improved if the health care industry adopted and reinforced these principles.

Remember when I said I was angry because what happened was not all Ms. Vaught’s fault? To date, no other VUMC employee or executive was disciplined or arrested for what happened to Ms. Murphey. Had VUMC management implemented any of these safety principles, management would never have told the hospital staff to override safety protocols in the medication dispensing cabinet. Management should have fixed the problem immediately or advised the staff that patient safety was too important and staff needed to be more patient—the increased risk of harm to patients is not justified by the loss of a few minutes. Ultimately, I am very disappointed that Ms. Vaught was the scapegoat, and no one punished the hospital’s managers and executives for Ms. Murphey’s death.

The biggest hurdle to such a dramatic change is money—profits are too important, and doctors and executives want to make a lot of money. This Phoenix Medical Malpractice Attorney hopes to change things.

Gage Mathers Law Group Attorney Named to the 2025 Arizona Super Lawyers List We are pleased to announce that Joseph D'Aguanno, the managing attorney at Gage Mathers Law Group, PLLC, has been selecte...

Posted by Joseph D'Aguanno

Do I Have A Medical Malpractice Case? If you were injured because your healthcare provider was negligent in their care and treatment of you, you might have a medical malpractice case. Common...

read morePosted by Joseph D'Aguanno

What to Do After an Accident: The Personal Injury Roadmap Being in an accident can turn your life upside down in seconds. One moment you’re driving to work, picking up groceries, or heading ho...

read moreIf you or a loved one has been seriously injured, please fill out the form below for your free consultation or call us at (602) 258-0646

2525 E Arizona Biltmore Cir #A114, Phoenix, AZ 85016

get directions